Essay

Poems of the Decade Essay Comparison of History and the Lammas Hireling

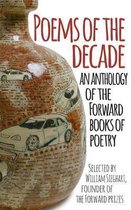

AQA A Level English Literature Poems of the Decade essay. I got 3 A*s at A-Level, 11A*/9/8 at GCSE, and I am currently studying History at the University of Cambridge. This essay features close detailed analytical comparison between History and The Lammas Hireling, reaching all the assessment obje...

[Show more]